by Arutz 7 Staff

April 16, 2020

Original Arutz 7 article posted at:

http://bit.ly/stories-of-the-2020-holocaust-memorial-torchlighters

Archive: Holocaust memorial torch (Photo: Yonatan Sindel/Flash90)

The state opening ceremony for Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Day will take place at 8 PM (Israel time) on Monday evening, 20 April.

This years ceremony will tale place in accordance to all cornavirus restrictions and rules. The event will be a pre-recorded ceremony without an audience which was filmed in the Warsaw Ghetto Square at Yad Vashem on the Mount of Remembrance in Jerusalem.

The central theme for this year's commemorative ceremonies and events is "Rescue by Jews during the Holocaust: Solidarity in a Disintegrating World".

Six survivors and one survivor representative will light torches during the ceremony, here are their stories:

Haim Arbiv was born in Benghazi, Libya in 1934, which was under Italian rule. The traditional family of nine lived in a mixed neighborhood of Arabs, Jews and Italians. At the end of 1940 the British launched an attack on Cyrenaica, the region that included Benghazi, and held it for several months until the Germans pushed them back out and reinstated the Italians. During the battles, Haim and his mother fled the city to seek shelter from the bombings.

After the Italians regained power, the treatment of Jews worsened since the authorities and the local Italian residents considered the Jews collaborators with the enemy. Jews in Benghazi were arrested and forbidden from engaging in commerce, and much Jewish property was confiscated.

In 1942, Haim's family was deported to the Giado concentration camp, 1,200 kilometers away from Benghazi. Before the horrific journey, his parents managed to hide gold coins inside loaves of bread, suitcases and belts, hoping it would help them survive. In Giado, every family received a small amount of living space inside a shack, with only bedsheets separating them. The food at the camp consisted mostly of meager, moldy bread. Hundreds of Jews died of hunger, fatigue and disease in Giado, among them Haim’s a newborn niece. Haim's immediate family avoided starvation thanks to his elder brother and sister, who bought bread from local Bedouins in exchange for the gold coins they had smuggled from home. This trade was very risky, because the guards would shoot whoever approached the camp fences.

After their liberation by the British army in 1943, the family returned to Benghazi. They rebuilt their destroyed home, and Haim attended a Hebrew-language school set up by soldiers from the Jewish Brigade. His connection to Eretz Israel grew stronger.

Late in 1947, as the fighting between Jews and Arabs in Eretz Israel intensified, Jews began suffering harassment in Libya. Haim’s grandfather was murdered by rioters. The family’s home was attacked, but an Arab neighbor fired a pistol to disperse the rioters and took Haim’s family into his home until tempers cooled.

In 1949, Haim and his family went to Tripoli and boarded a ship to Israel.

Haim is a volunteer chess teacher in kindergartens and senior citizens clubs. He has a son, a daughter and five grandchildren.

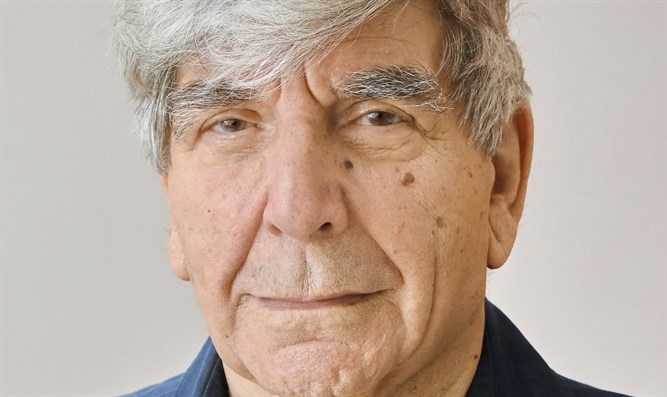

Haim Arbiv (photo credit: Photo: Israel Hadari)

Zohar Arnon was born in Kisvárda, Hungary in 1928 the middle child of Bina and Aaron’s five children. He attended a cheder, but at the age of ten he joined Hashomer Hatzair and became a Zionist. When he was 15, he went to Budapest to learn a trade.

On 19 March 1944, the Nazis occupied Budapest. In June, Zohar went to live with a friend in a house designated for Jews. He relied on his “Aryan” appearance and walked about without wearing the compulsory Star of David badge.

Zohar went to the offices of the Jewish community of Budapest to figure out what happened to his family members who had stayed in Kisvárda. There he met Efra Agmon, his group leader from Hashomer Hatzair. Agmon told him that he had been in Kisvárda and told the young people to escape, but they refused because they believed that the penalty for running away would be the murder of their entire families. Agmon asked Zohar, “Are you ready to go on a journey that will end in Eretz Israel?” Zohar responded in the affirmative, and Agmon gave him dollar bills and instructions to wait across from the train station the next evening. Zohar arrived there at the specified time, but he did not see Agmon. Suddenly a man wearing the uniform of a Hungarian train police officer approached him. Zohar recoiled, but the officer grabbed him and asked, “Don’t you recognize me? It’s me, Efra.”

Agmon was a member of the underground Zionist movement in Budapest, which provided thousands of young Jews with false papers and smuggled them into Romania. He gave Zohar false papers, and instructions to buy a ticket to Nagyvárad, near the Romanian border. During the train ride, two gendarmes boarded the train. Zohar feigned a stomachache and went to the bathroom. When he emerged, he was wearing the clothing of a Hungarian youth group. The gendarmes questioned him, and then left him alone.

Zohar traveled through Romania, Bulgaria, Greece, Turkey, Syria and Lebanon. In January 1945, he finally arrived Eretz Israel. His parents and two of his sisters were murdered in the Holocaust.

Zohar fought in the War of Independence and eventually became a forest ranger, a producer and a director. Zohar and his wife Ahuva have two daughters.

Zohar Arnon (photo credit: Photo: Israel Hadar)

Yehuda Beilis was born in Kovno, Lithuania in 1927, the youngest of Eliezer and Chana’s three sons. The Germans occupied Lithuania in 1941, while Yehuda was living in the resort town of Palanga. He was imprisoned in a synagogue with other Jewish teenagers, where they suffered abuse.

In October 1941, Yehuda's family was sent to the Kovno ghetto. A few days later, they were taken with thousands of other Jews to the Ninth Fort, the site of the mass murder of Kovno Jewry.

Yehuda was pushed to the edge of a pit. He heard shots, and the murdered Jews fell into the pit bringing him down with them. When he regained consciousness, he found himself in pitch blackness at the bottom of the pit. He made his way out through the bodies, and ran away. He reached a forest home and begged for help. The residents tended his wounds, fed him and gave him clothes but, fearing for their lives, they asked him keep their deeds secret. Back inside the ghetto, Yehuda told the remaining Jews what had happened to him, but they could not believe him.

After the daring prisoner escape from the Ninth Fort in late 1943, the Germans stepped up the search for Jews who were in hiding. On his brother's advice, Yehuda returned to the ghetto.

In March 1944, hundreds of children in the ghetto were abducted and murdered by the Germans. A few parents managed to hide their children, and the Judenrat sought to smuggle them outside the ghetto. They asked Yehuda to petition his friend, Father Stanislovas Jokubauskis, for help. Yehuda slipped out of the ghetto and found the priest, who agreed.

The plan entailed giving Yehuda a sack with a sleeping child inside, as well as money and cigarettes. He would leave the ghetto with the sack, bribe the SS guards, and go to the rendezvous point with the nuns sent by Father Jokubauskis. They would take the child to a hideout. In all, Yehuda smuggled 22 children out of the ghetto. Father Jokubauskis and Gene Jonusiene-Premeneckaite were later recognized as Righteous Among the Nations.

In the summer of 1944, upon the liquidation of the Kovno ghetto, Yehuda and his brother Yosef were sent to Dachau and put to work in the Kaufering labor camp. Yosef didn't survive, and Yehuda was left alone in the world.

In 1946, Yehuda immigrated to Eretz Israel. He joined the IDF and fought in the War of Independence. He regularly gave testimony about his experiences during the Holocaust. He and his wife Ahuva have two daughters, four grandchildren and five great-grandchildren.

Yehuda Beilis (photo credit: Photo: Israel Hadari)

Aviva Blum-Wachs was born in Warsaw in 1932 to Abraham (Abrasha) and Luba Blum née Bielicka. Abrasha was a leader of the Bund, the Jewish socialist workers’ party, and Luba was the deputy director of a nursing school. Aviva and her little brother Olek received their education from their Christian maid, spoke fluent Polish and knew the Christian rites. This helped them survive the war.

During the Great Deportation of the summer of 1942, the residents of the ghetto nursing school were marched to the Umschlagplatz, the departure point for deportations to the death camps. Luba managed to convince the Germans that the nurses were essential to the efforts to deal with the epidemics in the ghetto. The Germans let the nurses go, and Luba smuggled Aviva and Olek out in a vehicle used to carry corpses away from the Umschlagplatz.

In the Aktion of January 1943, the Germans barged into the hospital at 33 Gęsia Street and shot hundreds of patients, physicians and nurses. Luba had received a few minutes’ warning from the underground resistance, and managed to hide several of the nurses and patients, as well as her children, in the basement. Luba decided to smuggle her children out of the ghetto; first Olek, and several weeks later Aviva, who hid among a group of Jews who worked outside the ghetto. She went to Aurelia Borkowska, a poor and isolated laundress, who found a family that hid Aviva for two months. After an informer revealed her place of refuge, Aviva was moved between a few hideouts for several months.

Luba escaped the ghetto by posing as a Pole. She went to Aviva’s hideout and told her that her father, who participated in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, had been arrested by the Gestapo and murdered. Luba and Aviva left Warsaw. With the aid of false papers claiming she was the widow of a Polish officer, Luba found work on a Polish estate. In the spring of 1944, Polish partisans attacked the estate, killed the owners and burned it down. Luba and Aviva fled back to Warsaw, where they survived until liberation under Polish identities. Olek also survived under a false identity, with Borkowska's extended family.

In the summer of 1944, Luba and Aviva were liberated by the Red Army. Aviva immigrated to Israel in 1950. Aviva is an artist who presents her paintings in exhibitions. She has a daughter, four grandchildren and ten great-grandchildren.

Avraham Carmi (photo credit: Isaac Harari/Yad Vashem)

Avraham Carmi was born in Krzeszowice, Poland in 1928, the only child of Bezalel and Lea Stolbach. After the German invasion, his family fled to his uncle Moshe Posner, who managed the Warsaw Jewish cemetery. Posner’s home had been destroyed in the bombings, and he let them and other families stay in a structure in the cemetery. Avraham got used to living in the cemetery, which had 30-40 funerals a day, and would play with the workers’ children. He celebrated his Bar Mitzvah in the cemetery’s synagogue with a meal of beets and potatoes prepared by his mother.

Avraham helped Lea to build the ghetto walls in order to meet the quota for a food ration card.

In the summer of 1942, while the deportations from Warsaw to the extermination camps were underway, the Germans came to search the cemetery. Everyone living there ran to hide in a bunker, but Avraham and his mother didn’t make it. They were taken, along with other cemetery workers, to the Umschlagplatz, the departure point for deportations. The Germans discovered Avraham’s relatives hiding in the cemetery, and shot them.

Moshe Gelbkrin, the cemetery watchman, was given permission to leave the Umschlagplatz in order to take care of burials. He took Lea, who pretended she was his wife, and smuggled Avraham out in a backpack. Avraham’s father was deported to Treblinka and murdered.

When they reached the cemetery, they buried the family members who had been murdered there during the Aktion. During the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in the spring of 1943, the Germans discovered their bunker and took the people hiding there to the Umschlagplatz. Avraham, his mother and his uncle Moshe Posner were sent to Majdanek, where Lea was murdered.

Avraham and Moshe were taken to a labor camp in Budzyn, where they worked in an aircraft factory. Moshe watched over Avraham, shared his food with him, held his hand at night and tried to give him hope. Avraham and Moshe were later sent to a forced labor camp in Radom, and then on a death march towards Tomaszów Mazowiecki, from where they were taken to Birkenau. During the selektion, Moshe told Abraham to stand up straight and pinch his cheeks so that he would look healthy and fit for work. From Birkenau, Avraham and Moshe were sent to various labor camps. Moshe, who covered for Avraham and saved him every step of the way, died of exhaustion and disease just two days before liberation.

In September 1945, Avraham immigrated to Eretz Israel. He fought to defend the Etzion Bloc during the War of Independence, and was taken prisoner by the Jordanians. After his release, Avraham worked in the Mikveh Israel Agricultural School and was an inspector in the Education Ministry. Avraham has given testimony and traveled to the camps in Poland numerous times.

Avraham and Rivka, who survived Bergen-Belsen, have three children, nine grandchildren and 23 great-grandchildren.

Leah Reuveni (photo credit: Photo: Israel Hadari)

Leah Reuveni was born in Iršava, Czechoslovakia in 1926, the eldest daughter of Elias and Halana, who raised a traditional family of nine. In 1929, her family moved to Antwerp, Belgium.

When the city came under aerial attack in May 1940, the family fled the city and Leah lost contact with her mother and two of her siblings. For eight months, Leah took care of her younger siblings and the household.

When she heard that her mother and missing siblings were in southern France, Leah went to the German command center and asked for a travel permit. The Germans authorized Leah and her siblings to travel to Paris, but forbade the father from leaving. Lacking any alternative, they bade their father goodbye and traveled alone by train, all the while fleeing from German soldiers and evading checkpoints.

German troops boarded the train at the station in Lyon. When they saw the restricted permit, they threatened to throw them off the train. Thanks to her courageous arguments, the Germans allowed them to continue on, and they found her mother in the southern city of Quarante. Their father joined them a few weeks later.

When Vichy police began taking away Jewish refugees in the city in the summer of 1942, Leah went to look for a new place for her family to live. She wandered on foot and by train, spending nights in train station waiting rooms until she came to the town of Chirac. There she met the mayor, who was willing to give them an abandoned house with no bathroom. Her youngest brother was born in Chirac.

In November 1942, Germany occupied southern France except for the area occupied by the Italians, and Leah’s father was arrested. Leah went to the local command center and asked for him to be released for a day, explaining that her mother was recovering from childbirth. Impressed with her boldness, the French commander approved the request. Leah and her father fled to Nice, which was under Italian occupation. Afterwards, Leah managed to smuggle her mother and siblings into the city, too.

In 1943, the Germans occupied the area of Nice, and Leah and her family fled again, this time with a group of refugees. Leah backtracked several times along the tortuous mountainous paths in order to help the elderly and women with children. Leah and her family reached the town of Borgo San Dalmazzo, where she contacted Father Don Raimondo Viale. The priest, who was later recognized as Righteous Among the Nations, smuggled Leah’s family into the forest, where they reached a monastery in the area of Florence.

In November 1943, the Germans raided the monastery. Leah remembered that the Hungarians were allies of the Germans, and convinced them that she and her mother were Hungarian gentiles who had lost their papers. Leah managed to save 15 other Jewish women in a similar manner.

Survivor Representative: Naomi Cassuto (photo credit: Noam Moskowitz)

Naomi Cassuto (née Cohn) was born in 1938 in Strasbourg, France, to Yehuda-Leo Cohn and Rachel Cohn (née Schloss), Jewish refugees who had fled Germany after the Nazi Party came to power. In France, Leo joined the Tzofim (Jewish Scouts) Youth Movement and became involved in, among other things, teaching about Judaism, the Hebrew language, the Bible, prayer and music.

In December 1939, Leo enlisted in the Foreign Legion and was sent to North Africa. While he was away, Rachel and Naomi moved to Muscat, a town located in the south of France. Upon Leo's return in 1940, he began to lead the Jewish Scouts Movement in the area. He organized the Scouts Choir, performing across southern France, including in front of non-Jewish audiences. That year, Naomi's brother, Ariel, was born.

Leo served as deputy to the director of the Jewish Scouts Movement in France, Robert Gamzon (Castor). When Gamzon charged Leo with managing a farm in the town of Luterk, the entire Cohen family moved to live there. Leo would travel between the various areas where Jewish children and refugees were hiding in the south of France. He would try to lift their spirits and provide them with whatever they needed. Leo also published an underground newspaper that was distributed in those areas where Jews were in hiding, as well as a youth newspaper, which fostered a zest for life as well as a love for Judaism and the Land of Israel, and the desire to settle and establish a Jewish homeland there.

In May 1943, the occupying Nazi authorities imposed laws banning activities of the Jewish Scouts; these prohibitions forced the movement and their activities underground. The Luterk farm was dismantled, and the family once again moved to another town in the south of France, named Custer. There, Naomi's sister, Aviva, was born in 1944.

Leo's activities brought Naomi and her family to the Swiss border. Members of the underground tried to persuade Leo to cross the border together with his family, but Leo was chosen by the Jewish Scouts leadership to lead a group of youths from France to Spain. He decided to stay with the youth and transport them to Spain and from there to immigrate to Israel. Naomi recalls, "Before we separated, my father blessed me with God's blessings and promised that we would see each other again in the Land of Israel."

On 2 May 1944, Naomi and her family crossed the border from France to Switzerland. Leo remained in France and continued his activities organizing the rescue of Jewish youth by smuggling them to Spain. Two weeks after parting with the rest of his family, Leo was captured by the Gestapo. He was detained in the Drancy transit camp and after a few months was deported on Transport 77 to the East, where he was murdered in one of the concentration camps.

Naomi and her family immigrated to Israel in 1945. Her mother remarried.

Naomi received a doctorate in Art History. She worked for the Ministry of Education in the field of teaching practical and theoretical art. She also coordinated art curricula, specializing in paper cutting. Naomi curated various exhibitions in Israel, and served as a guide at numerous art sites around the world.

Naomi and her husband David have children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Return to Life in Israel Articles

Return to Life in Israel Articles Return to Only in Israel

Return to Only in Israel