Yad Vashem

May 5, 2024

2024 Holocaust memorial torchlighters

Each year, during the official Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Day ceremony that takes place at Yad Vashem, six torches, representing the six million Jews, are lit by Holocaust survivors. The personal stories of the torchlighters reflect the central theme chosen by Yad Vashem for Holocaust Remembrance Day. Their individual experiences are portrayed in short films screened during the ceremony.

Here are the stories and photos of the Torchlighters 2024:

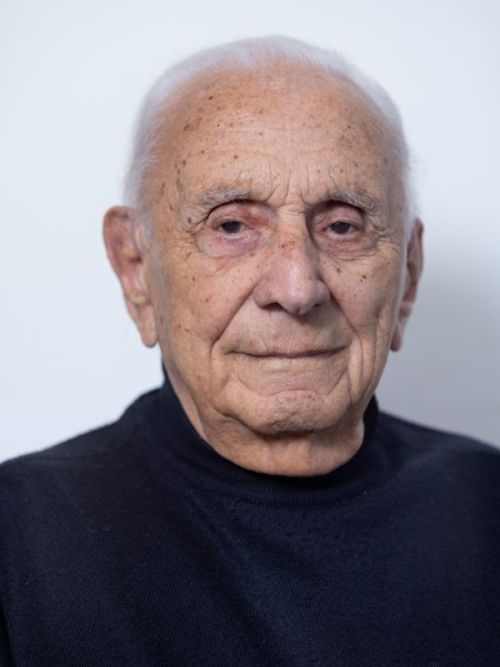

Michael Bar-on

Born Michael Brownfeld in 1932 in Kraków, Poland, Michael was the youngest of his Hasidic family's eight children. His father Haim was a merchant who led the prayers in the court of the Admor (spiritual leader) of Sanz, and his mother Nechama was a housewife.

After the occupation of Kraków by the Germans in September 1939, the occupiers abused Haim and tore off his beard and sidelocks. In 1941, the family was incarcerated in the Kraków ghetto before they were transferred to Międzyrzec Podlaski, where they lived in a stable due to lack of funds.

When a typhus epidemic broke out there due to the overcrowding, contamination, and hunger, almost all of the Brownfelds contracted the disease. Haim succumbed to typhus, followed two weeks later by Nechama, who died in the synagogue where the patients were being housed. Michael discovered that she had passed away after overhearing a random conversation in the street.

Posing as a Christian, Michael's cousin Bronka came to Międzyrzec Podlaski and smuggled Michael and his siblings to her hometown of Brzesko.

When rumors of the area's impending liquidation by the Germans started to circulate, Michael fled to the Bochnia ghetto and then to Kraków upon hearing about an upcoming Aktion. However, unable to enter the Kraków ghetto, he returned to the ghetto in Bochnia. From there, he fled southward to the town of Piwniczna together with his brother Elimeleh and their sister Aliza. They embarked on a grueling journey of almost 200 kilometers on foot, eventually reaching the city of Košice in Hungary (today Slovakia).

A few months later, the three siblings arrived in Budapest. Passing himself off as a Christian, Michael went to the Polish Consulate to obtain a document allowing freedom of movement to Poles. In April 1944, Michael, Elimeleh and Aliza escaped to Nagyvárad where they were confined in the local ghetto. Managing to smuggle themselves out of the ghetto, they reached their aunt Dvora, who lived in the city. From there, they fled to Romania but were caught and thrown into prison. Thanks to a bribe paid by a local Jew, the jailers released Michael and his siblings, and they went to Arad and then to Bucharest.

The three youngsters succeeded in boarding a boat that had anchored in the Port of Constanța in Romania and sailed to Istanbul in the hold. There, they boarded a train and reached Eretz Israel (Mandatory Palestine) via Syria and Lebanon in July 1944. They were arrested by the British and imprisoned in the Atlit detention camp. Upon their release, Michael was taken in by the Faltins, who fostered him and welcomed him with warmth and love.

Michael studied in the Agudat Yisrael educational institution in Magdiel, became a counsellor for young Holocaust survivors, and enlisted in the Israel Defense Forces. He held various command positions in the Israeli army and served as head of burial matters during the Yom Kippur War.

After twenty-five years in the IDF, he retired with the rank of lieutenant-colonel. During his military service, he was requested to Hebraize his family name and became Michael Bar-On.

After his retirement from the IDF, Michael was appointed deputy director of Administration and Personnel at Bar-Ilan University. Michael and his wife Haya have three children, and many grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Raisa Brodsky

Raisa (Rachel) Brodsky was born in 1937 in Sharhorod, Ukraine, to the Zubkovs, a traditional family of five. They spoke Yiddish at home, and Raisa's brother Senia studied in a traditional heder (Jewish elementary school). They observed the Jewish holidays and owned a special set of Passover dishes that Raisa's mother Molka stored in the boidem (crawl space). The family attended prayer services at the Great Synagogue, one of approximately ten synagogues in the town, as each workers' union established its own synagogue. As well as the traditional heder, the Jewish community in Sharhorod also opened Jewish schools, despite the efforts of the communist regime to restrict religious education. The town's residents would mark special events in the restaurant where Raisa's father Zamvel worked and in which the Jewish community would gather.

When Nazi Germany invaded the USSR in June 1941, the restaurant was ransacked. The manager threatened to kill Zamvel if he didn't cover the losses. Both the Jews and the Ukrainians in the town were fond of the family and worked together to help him.

Zamvel and Molka were conscripted to forced labor. In early September 1941 the Germans passed control of Sharhorod to the Romanians, who established a ghetto in the town. Zamvel organized underground meetings in his house, and together with his Jewish and Ukrainian resistance comrades, they smuggled food, clothes, equipment, and medicine to the partisans. The leaders of the underground—the Jewish Malinsky and the Ukrainian Grechaniy—were caught, tortured at the Romanian headquarters, and executed.

Jewish deportees from Bessarabia and Bukovina in northeastern Romania were also incarcerated in the Sharhorod ghetto. A refugee family came to live with the Zubkovs, exacerbating their already cramped living conditions. In 1942, Zamvel contracted typhus. One of the refugees in the ghetto, Dr. Teich, smuggled medicines he had stolen from the Romanian headquarters to the partisans and also used them to treat Jews including Zamvel. Molka heard that homes housing typhus patients were being burned down with their inhabitants still inside, and when soldiers went door-to-door searching for typhus patients, she walked out toward them so that they would not enter the house and find her family. During this time, Raisa and her siblings huddled inside, crying. When Molka returned, her hair had turned white.

After the Red Army liberated Sharhorod in March 1944, Raisa studied mathematics and drafting, and she taught mathematics at the school run by the brother of Grechaniy, the Ukrainian partisan who had worked with her father during the Holocaust.

After the USSR permitted immigration to Israel in 1989, Raisa and her family realized Zamvel's dream and made aliya. Raisa did not know any Hebrew, but she studied at an ulpan (Hebrew language study framework) and within a year, she had passed the mathematics teacher training course and started working at an elementary school.

Raisa and her husband Semion met another survivor from Sharhorod who told them about the Zikaron Holocaust survivors' association. Raisa started telling her story to wider audiences and even stayed in contact with the schoolchildren who heard her testimony. She shares her memories with them and helps them with their history studies.

Raisa and Semion have two children, five grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren.

Arie Eitani

Arie Eitani was born Armin Guttman in Milan, Italy in 1927, the only child of Hungarian immigrants Samuel and Etel. Arie has happy memories of his childhood and recalls feeling very much a part of Italian society.

On the eve of World War II, Jews with foreign citizenship were forced to leave Italy. The family returned to Hungary and settled in the city of Eger. Arie was sent to heder (Jewish elementary school), where he learned Hebrew, laid tefillin (phylacteries), was called up to the Torah, and celebrated his Bar Mitzva. When he was a little older, he attended a state school.

In 1942, Samuel was conscripted to the Hungarian Jewish Labor Service. In May 1944, Arie together with his mother Etel, his grandfather, and the rest of his family were incarcerated in the Eger ghetto. Approximately one month later, they were deported to Auschwitz, and the entire family except for Arie was murdered in the gas chambers. Arie was imprisoned in the Gypsy camp at Auschwitz and then transferred to the Kaufering camp, where he was a forced laborer. He had to drag sacks of cement and corpses, and he witnessed suicides, murders, and the throwing of prisoners' bodies into an enormous pit.

Recalling one of the selections, Arie relates:

"We were forced to run naked in front of the SS officers. I didn't pass [the selection]! I don't know where I mustered the courage, but I took advantage of a split-second when no one was paying attention and crawled under the cattle cars. I got dressed quickly and joined the prisoners who had been found fit for work."

When Kaufering was evacuated, the inmates were sent on a death march. “Anyone who lagged behind, stumbled, fell, or moved out of formation was beaten or shot to death." Arie reached the Allach camp, where he contracted typhus and became a Muselmann, a living skeleton. He was sent to a barracks from which the corpses were collected and disposed of in a pit each morning.

When US Army soldiers liberated the camp, Arie was too weak to stand up. “I crawled around and made do with remnants of food strewn on the ground."

Arie returned to Eger and boarded the Ma'apilim (illegal immigrants) vessel Knesset Israel in November 1946. However, the British intercepted the boat and imprisoned its passengers in Cyprus. There, the camp fence triggered traumatic Holocaust memories for Arie. He ran away but was caught, put on trial, and sent to jail. “Once again I wore a prisoner's uniform, and once more I was not free."

Arie finally reached Eretz Israel (Mandatory Palestine) in 1947. He enlisted in the Haganah and fought in the War of Independence, including in Mishmar Hayarden, which was attacked by the Syrians in June 1948.

"I was worried that my friends would mock me, a Diaspora Jew who was still on the run, like in the Holocaust. My friend Avraham Kasten and I decided that we would detonate the last grenade when the Syrians arrived. In those moments, my entire life flashed before my eyes. We could hear the cries of the approaching Syrians in the background. Suddenly, there was an explosion."

Arie was badly injured and was taken hostage. He was tortured, and some of his toes were amputated. He returned to Israel thirteen months later.

Arie is one of the founders of Kibbutz Ha'on in northern Israel. There, he met and married Rina, a Holocaust survivor from Poland.

Rina z"l and Arie have two children, eight grandchildren, and seven great-grandchildren. Rina passed away in 2020. Their first-born daughter Esther passed away in 2023.

Allegra Gutta

Allegra Gutta (née Naim) was born in 1928 in Benghazi, Libya. Her father Vittorio Naim was a merchant who owned a store in the city market. Allegra was the fifth child in the family and had nine brothers and sisters: Jamila, Julia, Yosef, Reuven, Dina, Shushana, Lydia, Eli and Fortune.

In April 1941, with the British retreat from Benghazi and before the arrival of the Italian armed forces, several Benghazi residents rioted against the Jews, looting Jewish homes and stores.

In early 1942, the Italians deported most of Benghazi's 3,000 Jews to the Giado concentration camp, over 1,000 kilometers west of Benghazi in the Libyan Desert. Allegra was deported with her parents and most of her siblings, except for her two older brothers Yosef and Reuven who managed to escape, enlisted in the British army, and served in Italy and Eretz Israel (Mandatory Palestine). The deportees were transported in trucks over several days, in the blazing heat and without receiving any food or water. Several died en route.

Allegra relates:

"We were in the Giado camp for one year and two months. The overcrowding was terrible, and we were starving. Many contracted diseases that broke out due to the contamination, such as typhus spread by lice. I took care of patients every day, including my father, who contracted typhus."

Allegra's father, her younger sister Fortune, and her older sister Jamila were among the hundreds of Jews who succumbed to typhus at Giado. Their bodies were left at the camp without a burial ceremony or a marked grave.

The British liberated Giado in 1943, and Allegra and her family returned to Benghazi. Allegra's two brothers were discharged from the British army and came back to Benghazi, where they repaired their destroyed home. The family once again lived in their beachfront house on Via Marina. Allegra helped to support her family by working at the British army canteen, where she learned English.

In September 1948, the Naims escaped to Tripoli in the dead of night and reached Naples, Italy, with the help of the Jewish Agency. From there, they took a train to Milan. In November 1948, the family sailed from Bari, Italy, to Israel on the Teti. They began life in Israel at the immigrant center in Binyamina before moving to Old Jaffa, and they finally settled in Holon a year later. In April 1952, Allegra married Aaron Gino Gutta z"l, and they made their home in Tel Aviv.

Allegra relates:

"As a Holocaust survivor, I try to live a full and active life. I am in daily contact with many friends, I am part of a group of Libyan-Arabic and Italian speakers, I exercise at the gym, play bridge, and enjoy my family. That is my victory over the Nazis."

Allegra and Aaron Gino z"l have two children, three grandchildren, and six great-grandchildren.

Pnina Hefer

Pnina Hefer was born in the village of Nuşfalǎu in Romania and had twenty brothers and sisters. Her father Anshel Asher Weiss was the community rabbi, and the family lived next to the synagogue. The Weiss family had a Zionist outlook and spoke Hebrew. Pnina's parents encouraged her to learn foreign languages and acquire general knowledge in addition to her Torah studies.

In 1940, Hungary gained control of the area, and when the Germans entered Hungary in March 1944, the Jews were subjected to abuse and restrictive decrees. Locals collaborated in these public acts of humiliation, but from time to time, one of their neighbors would still bring the family provisions that were forbidden to Jews.

In May 1944, the village Jews, including the Weiss family, were rounded up and sent to the Szilágysomlyó ghetto. They were herded into an open field, where they were forced to make tents out of their clothes. Jews were beaten and tied to trees. Beards and sidelocks were forcibly shaved, and the men were ordered to make sandals out of the straps of their tefillin (phylacteries).

Some three weeks later, Pnina and her family were deported to Auschwitz. On the train, her father told the children that if they were separated, they should make every effort to reach Eretz Israel (Mandatory Palestine). After exiting the cattle car, Pnina caught sight of her mother's haggard expression before they were separated at the selection. Most of the Weiss family were murdered in the gas chambers. Pnina was left with her sister Bluma.

Pnina and Bluma were in Auschwitz for five and a half months and experienced multiple selections. They bartered their bread rations for a prayer book that they hid, and they would pray with the other prisoners in their block.

In late 1944, Pnina and Bluma were transferred to Bergen-Belsen, where they fasted on Yom Kippur. They were sent to perform forced labor at an ammunition factory in Salzwedel and were liberated by US soldiers on April 14, 1945.

The sisters traveled to Yugoslavia and boarded the Ma'apilim (illegal immigrants) vessel Knesset Israel in November 1946. The British captured the boat and threw the girls' precious prayer book into the sea. A photograph of the two girls arguing with the British was published in a newspaper, and Pnina and Bluma were recognized by two of their brothers, who had survived and had already immigrated to Eretz Israel.

Pnina and Bluma were sent to Cyprus and eventually reached the Atlit detention camp in September 1947. Pnina moved to Jerusalem and studied at a teachers' seminary, finally fulfilling her childhood dream of being a teacher in Israel. She was eventually reunited with Bluma and four other siblings who had survived.

Pnina married Jacob, and they traveled to Tunisia as educational emissaries on behalf of the State of Israel. Later, they both taught at a Jewish school in Argentina, and when they returned to Israel, Pnina became the principal of the Masuot school in Bnei Brak.

Pnina is an active Holocaust survivor who tells her story to a wide range of audiences, and each year, she celebrates the day of her liberation together with her entire family.

Pnina and Jacob have three daughters, sixteen grandchildren, and more than forty-five great-grandchildren. Their three daughters have continued the family tradition and are also teachers, and all of Pnina's descendants live in Israel.

Izi Kabilio

Izi (Itzhak) Kabilio was born in 1928 in Sarajevo, Yugoslavia (today Bosnia and Herzegovina), the only child of Leon and Netta (née Birenberg). He attended the local Jewish school and the state gymnasium, was a member of the Hashomer Hatzair youth movement, and sang in the children's choir at the city's Great Synagogue. Leon owned a silk and wool factory that employed 250 workers and was one of the founders of the Jewish “Geula" bank, sitting on the board of directors until the bank's closure following the German invasion. On Passover, Izi's grandfather used to read the Haggadah in Hebrew and Ladino, and would tell him about Jerusalem. In January 1941, just months before the German occupation, Izi was scheduled to leave for Eretz Israel (Mandatory Palestine) through the Youth Aliyah but was pressured by his grandfather and mother to cancel his plans.

The Germans occupied Yugoslavia in April 1941. They nationalized Leon's factory, and Izi witnessed the destruction of the Great Synagogue by an unruly mob. The last seder night in Izi's grandfather's home during the occupation was a somber event, conducted by candlelight.

One of Leon's factory employees, a German mechanic by the name of Josip Eberhardt, was on friendly terms with him. After the German occupation, Eberhardt was recruited by the Gestapo but maintained his friendship with Leon.

In September 1941, the ultranationalist Croat organization Ustaša that ruled the Independent State of Croatia at the behest of the Germans deported Izi's grandparents to the Jasenovac camp, where they were murdered. Eberhardt came to the Kabilio home and escorted Leon, Netta, and Izi to his house, hiding them in the cellar. He obtained forged papers for them and smuggled them into the city of Mostar, which was under Croat civil rule and Italian military control. From Mostar, the Kabilios were continuously on the move and escaped to Split, but they were eventually caught and deported to a concentration camp near Dubrovnik. In March 1942, they were sent to a concentration camp on Rab Island.

After Italy surrendered to the Allies in September 1943, anti-Nazi partisans raided the island and ferried the Jews by boat to dry land. Izi and his parents reached the vicinity of Croatia, which had been liberated by the partisans. They went up into the mountains where they lived with the partisans. Izi fought in their ranks, and Leon made a Hebrew calendar so they would be able to mark the Jewish holidays.

At the war's end, Izi and his parents returned to Sarajevo. Izi graduated from the gymnasium and studied engineering. The Kabilios immigrated to Israel in 1948. Izi enlisted in the Israel Defense Forces and fought in a combat unit. He relates:

"At the first Independence Day parade in Jerusalem, my Hebrew wasn't good, but I stood erect with my rifle and saluted the flag, as the Holocaust flashed before my eyes. I said to myself: “This belongs to us now." "

Izi studied at the Technion and became an architect. For many years, he was actively involved in immigration to Israel, absorption, and Holocaust commemoration, serving as chairman of the Association of Survivors from Yugoslavia in Israel. Over the years, he has come to Yad Vashem frequently and told his story to a wide variety of audiences.

Izi and his wife Odeda have two daughters, Anat and Gilia, five grandchildren, and six great-grandchildren.

Life in Israel Articles

Life in Israel Articles