This discovery offers important insights on the connection between the biblical text and historical reality, the researchers said.

by Rossella TercatinJuly 13, 2021

Original Jpost article posted at:

https://bit.ly/3000-year-old-inscription

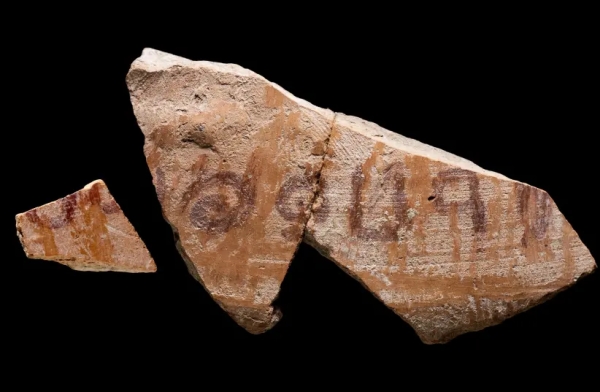

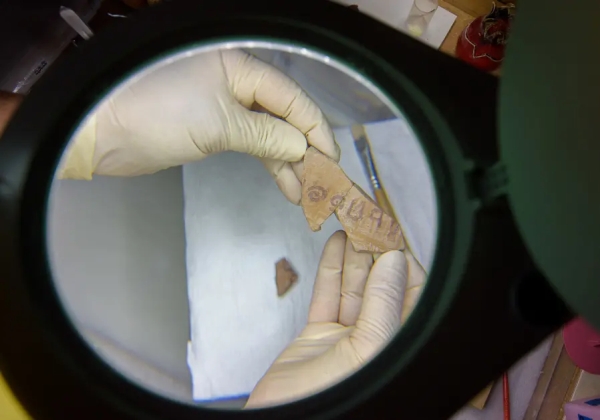

The Jerubbaal inscription, written in ink on a pottery vessel.

(photo credit: Dafna Gazit / Israel Antiquities Authority)

An inscription dating back some 3,100 years ago bearing the name of a biblical judge Jerubbaal was uncovered in the excavations at Khirbat er-Ra'i, near Kiryat Gat in the Southern District of Israel, the Antiquities Authority (IAA) announced on Monday.

The researchers highlighted that while there cannot be any certainty on whether the inscription refers to the figure mentioned in the Book of Judges, this discovery offers important insights on the connection between the biblical text and historical reality.

Inscriptions from that period - the 12th-11th century BCE - are extremely rare. All the dating has been carried out through both pottery typology and radiocarbon of organic samples found in the same archaeological layer.

The writing, inked on a jug, marks the first time that the name Jerubbaal has been found outside the biblical text. It is believed that the owner penned his name on the jug.

The Jerubbaal inscription, written in ink on a pottery vessel.

(Credit: Dafna Gazit, Israel Antiquities Authority.)

"The name Jerubbaal is familiar from biblical tradition in the Book of Judges as an alternative name for the judge Gideon ben Yoash," according to Prof. Yosef Garfinkel and archeologist Sa'ar Ganor from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Garfinkel and Ganor co-direct the excavations at the site with Dr. Kyle Keimer and Dr. Gil Davies from Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia - a partner in the dig together with the IAA.

"Gideon is first mentioned as combating idolatry by breaking the altar to Baal and cutting down the Asherah pole," they explained. "In biblical tradition, he is then remembered as triumphing over the Midianites, who used to cross over the Jordan to plunder agricultural crops. According to the Bible, Gideon organized a small army of 300 soldiers and attacked the Midianites by night near Ma'ayan Harod."

Aerial view of the excavation area where the inscription was found.

(Credit: Dafna Gazit, Israel Antiquities Authority.)

"Early next day, Jerubbaal - that is, Gideon - and all the troops with him encamped above En-harod, while the camp of Midian was in the plain to the north of him, at Gibeath-moreh," reads a verse in the 7th chapter in the Book of Judges.

Khirbat er-Ra'i has been excavated since 2015. According to Garfinkel, the site was already known from the survey conducted by British archaeologists in the 19th century.

The team decided to renovate the excavations because on the surface of the site they found pottery very similar to the artifacts uncovered in Khirbat Qeiyafa, an ancient fortified city from the time of King David - around 10th century BCE.

"We thought we might find another fortress, but instead we only found six rooms dating back to that period, so it looks like at that point it might have been just a small village," the archaeologist said.

However, it turned out that that site appeared to have reached its height one or two centuries prior, that is, at the time of the Judges.

Khirbat er-Ra'i is located close to an important archaeological site, where a center, Lachish, often featured in the Bible, once stood. In the middle of the 2nd millennium BCE Lachish was a prominent Canaanite city. According to the Book of Joshua, shortly afterwards it was destroyed by the Israelites as they conquered the Land of Israel at the end of their wanderings in the desert following their Exodus from Egypt.

The Philistine city of Gath was also close by.

Based on the archaeological findings, including the architecture and the pottery, Khirbat er-Ra'i was mainly a Canaanite site, but with a strong Philistine influence, according to Garfinkel.

"I believe that the site was mostly inhabited by Canaanite refugees, who came to live under Philistine hegemony" he said. The inscription, which was deciphered by the epigraphic expert Christopher Rolston of George Washington University, bears five letters: yod (broken at the top), resh, bet, ayin, lamed.

While the names of the letters might sound familiar to Hebrew speakers, the alphabet was not the Hebrew alphabet, but rather an alphabet from which the Hebrew one would evolve from centuries later.

"The alphabetic script was invented by the Canaanites and the Egyptian influence right about 1800 BCE," Garfinkel noted. "They continued to use this script, which evolved from Egyptian Hieroglyphs in the Late Bronze Age [1500-1200 BCE] and Iron Age I [1200-1000 BCE]. The Hebrew and Phoenician scripts were developed only in the middle of the tenth century BCE."

The fact that the cultural affiliation of the site was not Israelite does not exclude that the inscription was referring to the Jerubbaal mentioned in the Bible. The researchers stressed that there cannot be any certainty in one direction or in another. But even if the name actually referred to another Jerubbaal, the artifact still sheds important light on the connection between the biblical text and the period it describes.

"In view of the geographical distance between the Shephelah and the Jezreel Valley, this inscription may refer to another Jerubbaal and not the Gideon of biblical tradition, although the possibility cannot be ruled out that the jug belonged to the judge Gideon," Garfinkel and Ganor said. "In any event, the name Jerubbaal was evidently in common usage at the time of the biblical judges."

"As we know, there is considerable debate as to whether biblical tradition reflects reality and whether it is faithful to historical memories from the days of the Judges and the days of David," they added.

Prof. Garfinkel and Ganor at Khirbat er-Ra'i.

(Credit: Yoli Schwartz Israel Antiquities Authority)

Jerubbaal only appears in the Bible in the period of the judges, Garfinkel and Ganor remarked and yet "now it has also been discovered in an archaeological context, in a stratum dating from this period."

"In a similar manner, the name Ishbaal, which is only mentioned in the Bible during the monarchy of King David, has been found in strata dated to that period at the site of Khirbat Qeiyafa," they further said referring to a previous discovery they authored.

"The fact that identical names are mentioned in the Bible and also found in inscriptions recovered from archaeological excavations shows that memories were preserved and passed down through the generations," Garfinkel and Ganor concluded.

Only in Israel Index

Only in Israel Index

Life in Israel Articles

Life in Israel Articles